Working to improve mutual understanding between the Middle East and the West

Working to improve mutual understanding between the Middle East and the West

No products in the basket.

The 1923 Treaty of Lausanne may have been the last of the post-World War One peace settlements, but it was very different from Versailles. Like its German and Austro-Hungarian allies, the defeated Ottoman Empire had initially been presented with a dictated peace in 1920. In just two years, however, the Kemalist insurgency turned defeat into victory, enabling Turkey to claim its place as the first sovereign state in the Middle East. Meanwhile those communities

who had lived side-by-side with Turks inside the Ottoman Empire struggled to assert their own sovereignty, jostled between the Soviet Union and the resurgence of empire in the guise of League of Nations mandates. For 1.5m Ottoman Greeks and Balkan Muslims, ‘making peace’ involved forced population exchanges, a peace-making tool now understood as ethnic cleansing.

Chapters consider competing visions for a post- Ottoman world, situate the population exchanges relative to other peace-making efforts, and discuss economic factors behind the reallocation of Ottoman debt as well as refugee flows and oil politics. Further chapters consider Arab, Armenian, American and Iranian perspectives, as well as the long shadow cast by Lausanne over contemporary politics, both inside Turkey and out.

Jonathan Conlin is Professor of Modern History at the University of Southampton, and author of Mr Five Per Cent (2019), a biography of Calouste Gulbenkian.

Ozan Ozavci is Assistant Professor of Transimperial History at Utrecht University, and author of Dangerous Gifts (2021). He and Conlin founded The Lausanne Project in 2017.

| Weight | 1 kg |

|---|

Introduction

Jonathan Conlin and Ozan Ozavci

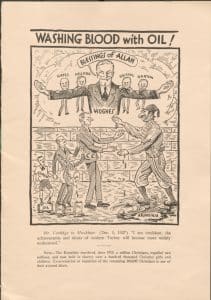

They All Made Peace

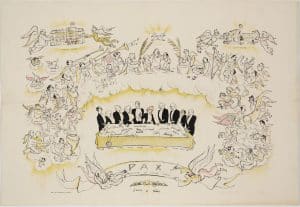

Founded in 1961, the War of Independence and Republic Museum (Kurtuluş Savaşı ve Cumhuriyet Müzesi) in Ankara is housed in the building of the first Turkish National Assembly. An object lesson in patriotic commemoration, the museum tells the story of the nation’s resistance to the Entente Powers’ attempted partition of Anatolia after the First World War. In 1920 the defeated Ottoman Empire seemed doomed to be reduced to a small Anatolian rump under the terms of the Treaty of Sèvres (1920). Within two years that diktat had been rendered a dead letter, thanks not only to the defeat of Greek, Italian and French military forces by the nationalist army of Mustafa Kemal (hereafter Atatürk), but an equally significant (and equally violent) exercise in reorienting political, religious, ethnic and class loyalties towards a new, secular Republic of Turkey. And so the museum’s medals and weapons jostle with prayer beads and identity cards. The prize exhibit is a table, displayed in the second room on the left, in the old Legal Commission room.

Measuring 360cm long and 76cm wide and covered with a dark red broad- cloth, this was the table on which the Lausanne Treaty was signed in 1923.1 It was brought to Ankara in 2008 as part of a state visit by the President of the Swiss Confederation, travelling in the luggage of the Swiss Army Orchestra. The Lausanne table was formally presented to then Turkish President Abdullah Gül on 11 November, at a concert given at Türk Ocağı Sahnesi (the Turkish Hearth Stage). As well as demonstrating that ‘the Swiss Army can both carry a table and make [good] music,’ for President Pascal Couchepin the sturdy table symbolised the strength of this bilateral relationship.

Eighty-six years before, Couchepin’s predecessor Robert Haab formally opened proceedings at the Near East Peace Conference summoned to the Swiss resort of Lausanne on 20 November 1922. For Haab, the battles of Sakarya and Dumlupınar were immediate and yet remote: even as he ‘bowed’ to those Greeks and Turks who had patriotically given their lives ‘up to some weeks ago’, their valour evoked heady tales of earlier ‘innumerable and bitter fights, recounted to us in the legends of ancient times and the chronicles of the Middle Ages.’ It had been war, and it had been ruinous. But now it was time to make peace. As a neutral country, helping conclude international agreements was ‘an attitude and a policy which are for us [the Swiss] a holy tradition.’

Lausanne had not been the first choice of venue. The Ankara government had proposed Izmir (Smyrna), a symbolic yet, as British Foreign Secretary George Nathaniel Curzon noted, somewhat impractical suggestion. Much of that great Ottoman entrepôt’s core had recently been incinerated as the Turks drove the Greek Army into the sea. Beykoz (at the northern end of the Bosphorus), Rhodes, Istanbul, Venice and Paris were considered. Experience of negotiating in Paris in 1919 had left many British diplomats disgusted with what they perceived as a venal French-language press. To this Curzon added a distaste for the ‘Levantines’ populating some of these cities. Venice emerged as an ideal option due to its location. But then, like Venice, Lausanne was on the route of the Simplon Orient Express, allowing easy access from Istanbul. Unlike Venice, which would give nominal leadership to Italian Prime Minister Luigi Facta (busy with Benito Mussolini’s fascists), Lausanne would not favour any one delegation.

For all Haab’s rhetoric of neutrality, Lausanne was hardly an Archimedean point. Foyers Turcs and their Armenian, Syrian and other equivalents not only served expat communities living and working inside Switzerland. They supplied a focus for continental diasporas. Switzerland’s universities had provided education and networking opportunities to generations of Pan-Islamists, Young Ottomans, socialists and communists, from Lenin and Mussolini to the Young Turks and the Armenian revolutionaries. Swiss banks provided boltholes, too. During the war, Deutsche Bank stashed its Bagdadbahn and associated oil interests in the Zurich-based Bank für Orientalische Eisenbahnen. To this day the funds (and archives) of the famed Committee of Union and Progress (CUP), the party which seized power in Istanbul in 1908 and led the Ottoman Empire into World War One, may well slumber in another of the city’s many banks, silently earning interest for unknown (and probably unconscious) beneficiaries.

As the history of Nestlé shows, however, Switzerland was not just a provider of education and financial services to Middle East elites: it was a source of consumer goods and, eventually, direct investment. Swiss neutrality certainly helped Nestlé escape pre-1914 Ottoman embargoes of other European manufacturers and win army contracts to supply Ottoman forces with condensed milk. In 1927 Nestlé opened a chocolate factory in Istanbul, which allowed it to exhibit its wares at trade fairs alongside signs urging visitors to ‘Consume Local Goods!’, parroting a mantra of Turkish economic nationalism.

Though highly distasteful to career diplomats like Curzon, master of ‘old diplomacy’, one of the aims of this volume is to tear down the barriers between diplomatic history and other sub-disciplines: to view the press, faith groups and humanitarians, bankers and multi-national enterprises as more than interlopers. Our focus is trained here not only on the statesmen and diplomats that sat around the negotiation table: the Turkish, British, French, Greek, American (as ‘observ- ers’), Italian, Romanian, Yugoslavian and Japanese plenipotentiaries, joined on occasion by Belgian, Soviet, Ukrainian, Georgian, and Bulgarian delegates. What happened beyond and below the table, in the rooms next door, which teemed with a plethora of non-governmental actors, is also discussed in the following pages. We will highlight how economic and financial considerations informed political, legal, diplomatic and humanitarian decision-making processes, and vice versa.

In addition to highlighting these inter-sectoral diplomatic dynamics at Lausanne, we offer a contrapuntal reading of the episode, to expose the ‘absent presences’, the unheard as much as the heard, their manifold interests, expectations, frustrations and resentments.8 Even though their delegations were not officially granted an audience, Lausanne was thronged with figures claiming to speak for Arabs, Armenians, Assyrians, Jews, Iraqis, Egyptians, Kurds, Nestorians, and other communities. As Laura Robson observes, surprisingly few of these aspired to their own Western-style nation-states (‘national homes’), such as those promised to Armenians and Kurds under the Treaty of Sèvres. Sarah Shields’ contribution to this volume argues that some Kurds sought to resist inclusion in any nation-state or empire, content to remain within ‘borderlands’. While all these communities looked to make peace, peace meant different things to different groups, and many communities were internally divided on what peace looked like to them.

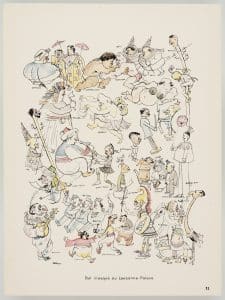

The observations of the caricaturist Emery Kelen, who found himself in Laus- anne in 1922 almost by accident, are particularly telling here. This Jewish ‘boy from Györ’ (Austro-Hungary) had been thoroughly worked over by history, then cast adrift with ‘three and a half years of world war in my bones, and three revolutions, pink, red, and white’ – as well as a salami, Kelen’s principal means of support until an Egyptian journalist, Mahmud Azmi, spotted him sketching Mussolini in Lausanne’s Beau Rivage. Buying the sketch for his satirical weekly Al-Kashkul (literally ‘The Begging Bowl’), Azmi Bey started Kelen on a career as court jester to the corps diplomatique. As Julia Secklehner demonstrates in this volume, Kelen and his partner Alois Derso (also in attendance at Lausanne) proved adept at interpreting Lausanne diplomacy for audiences across the world. Looking back forty years later, Kelen described an epiphany others shared, but failed to express so evocatively:

It seems to me that I can spy the very spot where Britain’s glory began to seep away into the dark; and I was there. It was in the third-rate hotels and crumbly family pensions of Lausanne, where the scent of insecticide and dust blended so happily with that of poulet rôti, pommes rissolées. There a penny-pinching caricaturist found his natural home among others of wobbly social status: Shi’ite mullahs from Persia, Sunnis from Iraq, Wahabis from the Hejaz, Zionists from Palestine, Kurds, Azerbaijanis, Macedonians, Gurkhas, Laks, and Lurs, who milled, swarmed, and plotted in an incessant rumbling, grumbling, undershudder to history. Each afternoon they would come to the surface and continue their sinister conspiracy to the tune of music at the thé dansant in the lobby of the Lausanne Palace Hotel. Like a viceroy reviewing native troops, Lord Curzon progressed through the lobby, staring with glassy eyes past the ragtag and bobtail that cluttered the plush-carpeted floor. Yet, in three decades, how many of these scrubby characters were to become sparkling ambassadors, or prime ministers of independent countries … holding appalling fate in their hands!

Kelen sketched those gathered around the famous Lausanne conference table, but also peeked below, spotting ‘the little brother of the conference table’: the green baize footstool provided for the chief British delegate Curzon’s gout. A towering physical presence loomed above the table while, below, rebellious extremities were painfully propped up. Curzon really was a synecdoche for an empire then facing unrest in Egypt, Iraq, and India, thanks to the efforts of Saad Zaghloul, Simko Shikak and Mahatma Gandhi.

As Curzon noted to a colleague, ‘hitherto we have dictated our peace treaties’. Yet at Lausanne he found himself ‘negotiating one with the enemy who has an army in being while we have none, an unheard of position.’ Though all agreed that Lausanne witnessed a dramatic shift in the perceived balance of power, there was little consensus on who exactly the ‘winners’ and ‘losers’ were. For Kelen it marked the beginning of the end for Britain. For Basil Mathews of the London Missionary Society, it was ‘the old authority of the white man’ which had received its ‘coup de grâce’ at Lausanne, as ‘the Turkish people (totalling little more than the population of Greater London) … dictated terms to the world-powers’, a process allegedly followed closely ‘in every bazaar in India, by the night-fires of Arab sheiks, and in student debates from Cairo to Delhi, Peking and Tokyo.’ Lausanne was a story of ‘the clash of civilisations’: ‘white man’ on one side, ‘Young Islam’ on the other. The British historian A.J. Toynbee preferred ‘contact’ to ‘clash’ but was equally persuaded that Lausanne represented a turning point in the history of ‘civilisations’: the point where the ‘Eastern Question’ became The Western Question, where orientalist sifting of empires into nation states gave way to recognition of the barbarous occidentalism visited upon the ‘East’ in the name of this ‘Westernisation’.

Within Turkey the legacy of Lausanne was immediate as well as enduring. From the moment the Turkish delegation signed the treaty on 24 July 1923, a Tuesday, at nine past three in the afternoon, it has been used as a trope to further political ends at the hands of Kemalist and (neo-) Ottomanist writers. As Hans- Lukas Kieser has noted in this volume (and in other publications), four members of the Turkish delegation later joined the Türk Tarihi Tetkik Cemiyeti (Turkish Historical Society) established in 1930.14 ‘[Lausanne] not only contributed to rewriting contemporary history,’ but laid the foundations of the Turkish History Thesis of the 1930s, that in turn presented the Turks as “proto-European” originators of human civilisation. Building on previous work by Fatma Müge Göçek, Gökhan Çetinsaya’s discussion here ranges across historical as well as politi- cal discourse since 1923, showing how Turkish perceptions of Lausanne lurched from one extreme to the other, from a heroic victory marking the end of five hundred years of European meddling to ‘Turkey’s unconditional surrender to the West’. When the Lausanne table arrived in Ankara, the conservative paper Vakit (Time) deplored it as an ‘execution table’ on which the Turks ‘lost an empire!’ Here we trace the origins of today’s conspiracy theories (espoused by 48% of Turks, according to a 2018 survey), which claim 2023 will see the revelation (and expiration) of Lausanne’s ‘secret clauses’. Though entirely without foundation, the authority enjoyed by analogous theories in many other nations makes the exploration of their origin and function especially urgent, a task in which social anthropologists and historians can usefully collaborate.

Outside Turkey (and to a lesser extent Greece), Lausanne has received little scholarly attention from historians. This in contrast to anthropologists such as Renée Hirschon, whose study of Ottoman Greek refugees in Piraeus led to ground- breaking works such as Heirs of the Greek Catastrophe (1989) as well as an edited volume Crossing the Aegean (2003), which included important contributions from historians as well as anthropologists. In 2011–2012 the Benaki Museum in Athens curated a series of exhibitions, films and other projects exploring the legacy of the exchange. In his comparative analysis of modern international systems Eric Weitz nonetheless laments that ‘it is barely known today except to specialists on the region.’ Though Zara Steiner echoes earlier British diplomatic historians in noting that Lausanne ‘proved to be the most successful and durable of all the post-war settlements’, her magisterial study of inter-war diplomacy only grants the conference two pages. Other than Sevtap Demirci’s 2005 monograph, itself focussing on the strategic calculations of Britain and Turkey, there is no scholarly volume dedicated to Lausanne in the English language. Indeed, the much less significant 1922 Genoa Conference has received more attention from scholars. Scholarship seeking to re-examine the familiar narratives of 1914-1918 by situating them within a ‘greater war’ that began in 1911 (with the Italian invasion of Ottoman Tripolitania) and ‘failed to end’ in 1918 – to cite Robert Gerwarth’s landmark The Vanquished (2016) – has entirely passed Lausanne by. This is so despite the fact that, as Gerwarth notes in his book, Lausanne ‘fatally undermined cultural, ethnic and religious plurality as an ideal to which to aspire and a reality with which – for all their contestations – most people in the European land empires had dealt with fairly well for centuries.’

Accounts of the ‘making’ or ‘creation’ of ‘the modern Middle East’ usually devote only a few lines to the Lausanne Peace Conference: David Fromkin ignored it entirely. As Elizabeth F. Thompson underlines in her chapter, it is equally com- monplace to overlook Lausanne’s part in ending ‘the political moment towards popular democracy in Greater Syria and elsewhere in the former Arabic-speaking territories of the Ottoman Empire.’ Frederick Anscombe and Michael Provence are notable exceptions to this cleavage between Arab and Ottoman history, empha- sizing a shared legacy of what the latter refers to as ‘Ottoman modernity’. This volume seeks to provide an equivalent for the raft of volumes addressing Ver- sailles, Trianon and other post-war settlements. It also seeks to restore Lausanne to the historiography of the wider Middle East, that ‘post-Ottoman’ space that Einar Wigen has dubbed ‘an area studies that never was’.

‘An important book offering new perspectives on the Lausanne Treaty of 1923. Gone is the positive interpretation of Lausanne as the most ‘successful’ of the treaties ending hostilities in the Great War; in its place is a multi- layered account of exploitation, exclusion, and betrayal of the promise of recovery and development in a region ravaged by war, famine, and genocide. These essays offer a new and important interpretation not only of Middle Eastern history but of international history in the 1920s.’

Jay Winter, Professor of History Emeritus, Yale University

‘Of all the international treaties signed after World War I, only Lausanne remains intact: the founding document of the Turkish Republic. Yet the Lausanne peace process has not attracted the interest it deserves. In the absence of well-grounded research, journalists and Islamist demagogues alike have come up with their own myths, myths that continue to circulate today. Here at last, a century on, we have the definitive work: of interest not only to diplomats, political scientists and historians, but the educated public in general.’

Ayhan Aktar, former Professor of Sociology, Istanbul Bilgi University

‘They All Made Peace—What is Peace? is a welcome addition to the literature on the 1923 Lausanne Treaty and the impact of the decisions made there that continue to resonate in present-day international politics. Long overdue, the volume represents a primer on a neglected and under-represented moment of post-imperial Ottoman history.’

Virginia H. Aksan, Professor of History Emeritus, McMaster University

Everything one needs to know about the Lausanne Treaty… and much more: the prelude and the aftermath, the winners and the losers, the powerful and the weak, the arrogant and the meek, the present and the absent, the loud and the silent, the players and the onlookers… 16 highly competent authors provide a remarkably thorough and exhaustive study of the international treaty which, a century ago, determined the fate of the future Republic of Turkey and redesigned the region surrounding it.

Edhem Eldem, Boğaziçi University, Istanbul