Working to improve mutual understanding between the Middle East and the West

Working to improve mutual understanding between the Middle East and the West

No products in the basket.

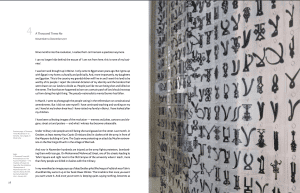

Part visual history, part memoir, You Can Crush the Flowers is the celebrated Egyptian-Lebanese artist Bahia Shehab’s chronicle of the Egyptian Revolution of 2011 and its aftermath, as it manifested itself not only in the art on the streets of Cairo but also through the wider visual culture that emerged during the revolution. Marking the ten year anniversary of the revolution, the book tells the stories that inspired both her own artwork and those of her fellow-revolutionaries. It narrates the events of the revolution as they unfolded, describing on one hand the tactics deployed by the regime to drive protesters from the street — from the use of tear gas and snipers to employing brute force, intimidation techniques and virginity tests — and on the other hand the retaliation by the protesters online and on the street in marches, chants, street art and memes. Throughout this powerful and moving account, and using a vast array of over 250 images, Bahia Shehab responds to what she has witnessed as both artist and activist. The result bears witness to the brutality of the regime and pays tribute to the protestors who bravely defied it.

Bahia Shehab is a multidisciplinary artist, designer and art historian. Her work is concerned with identity and preserving cultural heritage. Through investigating Islamic art history she reinterprets contemporary Arab politics, feminist discourse and social issues. She is Professor of Design at The American University in Cairo. Her book At the Corner of a Dream: A Journey of Resistance & Revolution – The Street Art of Bahia Shehab was published in 2019.

Asia House Podcast: Art, Revolution & People’s Voices

Interview with the Arab British Centre

Savoir dir non: French article on Bahia’s ‘A Thousand Times No’

Foreign Affairs review of the book

Cornelia Wegerhoff interviews Bahia Shehab for WDR 3 Culture Radio (German):

Introduction

Rooms in an Imagined Museum (January to February 2011)

The Calligrapher’s Headline (February 2011)

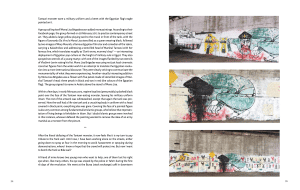

A State of Democratic Infancy (February to October 2011)

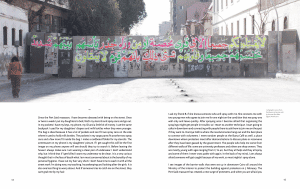

A Thousand Times No (November to December 2011)

First Anniversary (January to March 2012)

The Candidates (March to June 2012)

The New Pharaoh (July to December 2012)

The Children of Asyut (January to June 2013)

Rebel, Cat! (June 2013)

Stealing the Dream (June 2013)

A Conversation (July to October 2013)

Ten Years On: May You See Days Better than Mine

Introduction

I am not a rebel. When the revolution started on 25 January 2011, I was in Cairo watching the events unfold like so many others all over the world: on a screen. I was never in Tahrir Square during the first 18 days of the revolution. I neither smelled tear gas nor was beat- en with a policeman’s baton. Snipers did not take out my right eye. Armed thugs did not chase me with hatchets. My face was not the last sight seen by a dying stranger as I held him in my arms while he breathed his last. I never chanted for the ousting of Mubarak. I never served in a field hospital set up in a nearby mosque. My blood did not leave a trail on the asphalt for others to document and share on social media.

If I were to meet myself ten years ago, I would tell her: ‘Brace yourself! Everything is going to change. Not for the better and not for the worse. But inside you walls are going to come crashing down and you will walk out a free woman.’ To me this might be the most meaningful outcome of a revolution: it shakes our being and shifts the course of our lives. Because it is only in shifting an individual perspective that real change can ever happen, no matter how long it takes.

When I moved to Cairo in 2004, I wanted to ask my well-to-do friends who had been living in the country all their lives, how come their necks didn’t hurt from looking the other way every time they saw a pile of rubbish on the streets or a beggar knocking on their car window. How do you cope with seeing misery every time you walk in the city and how does it not affect your soul? How long does it take you to become desensitised? I suspected that each person must have developed their own logic and internal coping mechanisms, and that I would eventually develop mine.

When the revolution started, I thought that it had nothing to do with me. I was not born in this land and none of this is my business. I watched and documented as a historian and the outsider I believed I was. But the walls, they started falling, and I had to rationalise my actions and understand my reactions. I had to realise that the walls that were falling inside of me were bigger than my small self. We have been conditioned to accept what is unacceptable; to live in a society that has been groomed to give up on freedom in exchange for security; to accept poverty as a given and apathy as strength; to pray for the wrong gods and celebrate the wrong achievements. During the Lebanese civil war, I was taught never to discuss politics because doing so can get you killed. Walk close to the wall and mind your own business. As a human I learned that there were layers of oppression, and as a woman these layers become thicker.

When the walls fell, the world got smaller and not bigger as I had expected. I thought, as a prisoner of the ideas that were imposed on me by society, that this liberation would be the ultimate freedom. I never expected the burden to be so heavy. You being to see, and you realise that the chain of oppression runs long through history and it is a chain that continues up until today.

When the revolution started, I was alone. I had family and friends of course, but I was alone, or at least I felt that way. Those in my circles disregarded my questions at the time. Why are there children begging on the street? Why can’t I walk on a clean and even sidewalk? Why do I and other women have to think about what to wear ten times before we decide to step out of our doors for fear of harassment? Why can’t we drink clean water from our taps even though we live in a country with one of the biggest rivers in the world? Why are some of our most beautiful historic monuments in such a horrible condition and being destroyed? How can I escape the feeling of guilt when my fridge is full and others are hungry? Is it okay to have access to resources and to be safe yourself when others do not and are not? Why am I still sometimes regarded as an out- sider even though I have an Egyptian passport, have given birth to two Egyptian daughters and even speak with an Egyptian accent? And if I do not belong here nor back in Lebanon then where do I belong? And then there is the question my eldest daughter asked me when she turned seven: why can’t I (meaning herself) be president of Egypt?

After the revolution, the walls fell and the world got smaller. I will tell you the story as I saw it, but bear in mind that we were millions and this is only one point of view. Be- ing in Tahrir Square with a huge crowd is difficult to describe. Can you imagine being stripped of respect and dignity all your life, only for people to come together, in enormous numbers, numbers your city hasn’t seen come together in decades, to tell you that you deserve respect and dignity? In that coming together you regain everything that has been taken from you. Can you imagine standing in a square with so many people who are all asking for the same thing? I felt that my existence on this planet was finally justified. Even if now it all seems like an illusion, for a few months that same illusion felt real and emitted enough light to inspire the whole world.

Cairo, June to September 2020

Our work relies on the generous support of our donors. Any contribution, no matter how small, helps us achieve our aims.