Working to improve mutual understanding between the Middle East and the West

Working to improve mutual understanding between the Middle East and the West

No products in the basket.

Barbara Brend has devoted decades of forensic labour to the task of unravelling the complexities of these two fifteenth-century manuscripts of Nizami’s Khamsah in the British Library. In clear and elegant prose she explains what makes them great and how text and image illuminate each other. Her insights are by turns surprising, stimulating and compelling, and they are consistently fresh and original. Quite simply, this book is a treasure, and it takes the study of Timurid painting to new levels of sophistication.

Robert Hillenbrand, Emeritus Professor in Islamic Art History at the University of Edinburgh and Honorary Professorial Fellow at the University of St Andrews.

In this book, Barbara Brend provides an account of two very beautiful manuscripts housed in the British Library (Or.6810 and Add.25900). Both are copies of the Khamsah, a set of five poems by the Twelfth-century poet, Nizami, one of the most renowned authors of Persian literature.

Although well known, the manuscripts have never before been written about in relation to each other. Brend tells the story of each poem and the painting that illustrates it, and she formally analyses the images, placing them in their historical and artistic context. The images from both highly-prized manuscripts are beautifully reproduced in colour, and the collected history of one of the manuscripts—recorded in the form of seal impressions and inscriptions—is also included. Ursula Sims-Williams provides a translation and commentary of these important marks of ownership which identify the Mughal rulers Akbar, Jahangir, Shah Jahan, and Aurangzeb.

Barbara Brend is a specialist in the field of Persian and Mughal painting. Her most recent books include Perspectives on Persian Painting: Illustrations to Amir Khusrau’s Khamsah and Muhammad Juki’s Shahnamah of Firdausi.

| Theme | Art |

|---|

Acknowledgements

INTRODUCTION

CHAPTER 1—Herat and the Timurids

CHAPTER 2—The Painting Tradition of Timurid Herat

CHAPTER 3—Add. 25900, Manuscript and Illumination

CHAPTER 4—Illustrations in Add. 25900

CHAPTER 5—Or. 6810, Manuscript and Illumination

CHAPTER 6—Illustrations in Or. 6810

CHAPTER 7—Conclusions on Add. 25900 and Or. 6810

Appendix A— Break-lines in Add. 25900 and Or.6810

CHAPTER 8— Or. 6810: The Afterlife of a Manuscript

URSULA SIMS-WILLIAMS

Appendix B— Transcriptions of the Notes and Seals in Or. 6810:

URSULA SIMS-WILLIAMS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

INDEX

Introduction

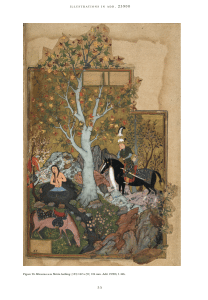

The British Library has two very beautiful manuscripts of the Khamsah (Quintet) of the twelfth-century poet Nizami, their illustration for the most part carried out ca. 1490–95 in Herat, under the rule of the Timurid Sultan Husayn Bayqara. The manuscripts are of fine quality and were made when the art of illustration was at a peak; we shall treat them with their British Library identifications, Add. 25900 and Or. 6810.1 The manuscripts are far from unknown and individual pictures have been much published and repeatedly discussed, but they have not hitherto been treated in full and in relation to each other. Their recent digitisation has been a powerful aid to study, though nothing can replace the presence of the actual volume.

The Khamsah consists of five books: Makhzan al-Asrār (The Treasury of Secrets) in which twenty moral discourses are each illumined by a brief parable; Khusrau va Shīrīn (Khusrau and Shirin), which relates the love story of a king of Iran in the pre-Islamic Sasanian period with a queen of Armenia; Laylā va Majnūn (Layla and Majnun) tells of separated lovers in pre-Islamic Arabia; Haft Paykar (Seven Fair Forms), in which the story of a Sasanian king, Bahram Gur, frames seven stories told to him by seven princesses; and Iskandarnāmah (The Story of Iskandar), which tells of Alexander the Great, first in the Sharafnāmah (The Book of Honour) devoted mainly to his worldly glory, and then in the Iqbālnāmah (The Book of Acceptance), which shows Iskandar’s advance into prophethood.

The manuscripts have had a life history of their own, though this is known in part only: Add. 25900 was evidently taken from Herat to Tabriz, and it would seem from there to India, the probable location of its passing into British hands in the nineteenth century; Or. 6810 was certainly present in the library of the Great Mughals in India and passed into British hands in the late eighteenth century. Both manuscripts were subsequently acquired by the British Museum and were transferred to the British Library in 1973.

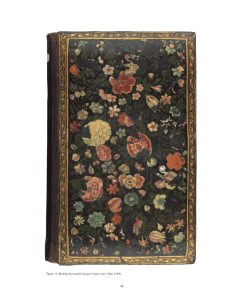

For some two centuries prior to the making of these two copies of the Khamsah, manuscript illustration had been practised in a way that was concentrated, conscious and discriminating, whether the book was for the delectation, education or solace of an individual, or to be passed round at cultured gatherings. In the literary sphere of late fifteenth- century Herat, references, quotations, impromptu verses, and riddles were to be expected, so we may look for their equivalents in painting. Poetry was permeated with Sufism, with the search for the Divine robed in many well-understood metaphors, but particularly in the lover’s yearning for the beloved. In many cases the readers would know the narrative contained in a volume from infancy: on the abstract literary side, the purpose of the manuscript might thus be to allow them to search for a favourite passage, while on the physical and visual side it would open the way for the admiration of calligraphy, illumination and painting—there would even be tactile pleasure from a fine leather binding.

For whom were these manuscripts made and by whom? Though there was commercial production at the time, the two manuscripts in question are of a princely level and so were evidently made on the order of specific patrons. The identity of the patron of Add. 25900 can only be a matter of speculation, while the names and titulature in Or. 6810 leave us in debate. Regarding their production, there was evidently access to the royal kitābkhānah (house of books), which functioned both as a library and repository for earlier works, and as a scriptorium and workshop for the production of new ones. In such an establishment, artists were employed by a king or a grandee. We know a little of the basis of payment but not much. We have the names of some scribes, though not for the present manuscripts, and of some artists—which will be a driver of discussion. Work might start with consultation between patron and senior calligrapher on what subjects were to be illustrated, and the latter would leave spaces in his copying of the text accordingly. The senior painter might be in a position to lay down how he wanted a page organised, where the text should stop and start. There would also necessarily be specialists in the production of paper, in illumination and the ruling of borders, and in binding. The present study is aimed primarily towards an understanding of the pictures, though the other specialities will be mentioned.

In order to attempt to appreciate the pictures in these manuscripts we need to have some grasp of the narrative, particularly at the moments selected for illustration. The painting is in the main guided by the text but occasionally a painter may diverge a little, either intentionally as he finds he has more to express, or accidentally if his notion of a very familiar subject has become a little eroded. The narratives are couched in couplets; the more meticulous or cautious painters would focus closely on the couplet immediately preceding the illustration, a position that has been called the ‘break-line’.2 Some subjects were chosen frequently over time and so the artist could, if he wished, rely on a tradition of depiction: the artist might be able to see a version of his subject in an earlier manuscript in the kitābkhānah, or he might have learned a standard iconography from a master, either by way of sketches or even verbally. The main intent was usually to convey the narrative, to express who and what was there, and what happened; it was not to evoke a visual impression as experienced by a particular beholder. In consequence pictures have a diagrammatic quality with each item seen with considerable clarity, even if it be night, and with distances contracted if they are not important. This is a realism of content and not the visual naturalism that conveys space, volume, and the play of light. Figures are dressed in the costume of their own day and surrounded by their contemporary accoutrements, though perhaps in idealised versions.

Though the main lines of the development of Persian painting are well charted, much of the detail is unclear, unproven or in debate. It therefore seems necessary, before beginning a discussion of these two copies of the Khamsah, to lay out a personal view of other manuscripts of the relevant period in order to give some indication of what is known information, what is common opinion, and what is more

slender hypothesis. Nowhere is the debate more a matter of hypotheses delicately balanced on one another, than in the matter of which painters of known name painted which pictures. Though some scholars have turned away from the study of individual hands, it seems to me that it should be pursued, both out of respect for the artists and because it is a useful tool to intensify the study of a picture. The artist’s name that is most widely found in relation to the period is that of Bihzad. When, in 1961, Basil Gray wrote of the ‘two wonderful manuscripts of the Khamsa of Nizami’, then in the British Museum, ‘each containing some miniatures which are generally accepted as the work of Bihzad’,3 the debate had already been in progress for some decades. Bearing in mind that the names of some other artists are available, the present work will try to argue towards more specific views, though definite conclusions may not always be achievable

NOTES

1 They can be seen at: http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/ FullDisplay.aspx?ref=Add_MS_25900 and http://www.bl.uk/ manuscripts/FullDisplay.aspx?ref=Or_6810

2 Farhad Mehran, ‘The Break-line Verse: The Link between Text and Image in the “First Small” Shahnama’, 151–69, especially 151, introduces the term as the verse that has ‘the closest association to the scene’, that is ‘often found immediately before the image’. In the present study, ‘break-line’ refers almost exclusively to the line before the image. The break-lines of the two manuscripts are listed in Appendix A.

3 Basil Gray, Persian Painting, 113.

‘For centuries these intimate images were gazed on by only privileged few. only now, with high-quality productions online and books such as this are they being opened up to the world. who has the right to look was an idea these artists played with. a sensual portrayal in (II) of ladies bathing draws us in with its voyeuristic gaze – until we are arrested by the single eye of a man watching through a slit in the window, clutching the shutter in excitement.’

–Sameer Rahim, Deputy editor of Prospect and the author of a novel, Asghar and Zahra (John Murray).

‘Brend’s Treasures of Herat performs a deep dive on the two manuscripts, providing unique insights in to the purpose and the means used to produce them. Both were probably destained to serve as prestigious diplomatic gifts. The choice of Nezami, a story-telling poet who combines pleasure with didacticism, would be consistent for this purpose. Readers would have known the text by heart. The enjoyment came from contemplating the familiar scenes and experiencing both confirmation with the expected and delight in the unexpected within the illustration.’

–David Chaffetz, Asian Review of Books

‘Barbara Brend confidently and engagingly explains the lineage and political connections of key figures at the Timurid court, providing an essential historical backdrop to her subsequent descriptions of the court painters and the paintings and manuscripts they produced. Illustrated manuscripts in this period were typically the joint output of multiple artists working within an atelier, not a single master artist, but she is nevertheless able to identify and explain the contributions of not only the eminent painter Bihzad, but also less well known figures such as Mansur and his son and pupil Shah Muzaffar, Darvish Muhammad, Mirak, and Qasim Ali.’

Sophie Ibbotson, Asian Affairs

Our work relies on the generous support of our donors. Any contribution, no matter how small, helps us achieve our aims.