Working to improve mutual understanding between the Middle East and the West

Working to improve mutual understanding between the Middle East and the West

No products in the basket.

£60.00

Art, Faith and Empire in Early Islam

by Alain George

Format: Hardback (240x290mm)

Published: June 2021

Pages: 260

ISBN: 9781909942455

The Great Mosque of Damascus is an iconic monument of world architecture, and the oldest mosque still standing in something close to its original state. This book is the first in-depth study of its foundation by the Umayyad dynasty, just as the first Islamic century was drawing to a close.

Towards the end of 705, the Umayyad caliph al-Walid determined to build a new monumental mosque at the heart of his capital Damascus. This required the seizure of a church that had stood there since the forceful closure, centuries earlier, of the Roman temple of Jupiter, the walls of which still stand today. When the Christians refused to cede their building, al-Walid decided to take it by force. This controversial act broke with the consensual politics of the early Islamic empire and triggered a major crisis, the ripples of which were felt as far afield as the Byzantine Empire. Still, events ran their course. Once the rubble of the church was cleared, al-Walid and his supervisors deployed complex logistics to create a building of dazzling opulence and splendour that marked a turning point in mosque architecture.

The book anchors the foundation of the Umayyad Mosque in its pre-Islamic past and brings to life the commotion that followed the destruction of the church. Alain George explores the process whereby craftsmen and materials were gathered to build the new mosque, seeks to reconstruct its Umayyad appearance, and investigates the subtle aesthetics that underpinned its stupendous ornament. This beautifully illustrated volume is based upon extensive research on new textual and visual sources, including Umayyad court poems and rare nineteenth-century photographs.

Alain Fouad George is I.M. Pei Professor of Islamic Art and Architecture at the University of Oxford. Born in Beirut, educated in France and England, he taught previously at the University of Edinburgh. His research focuses on early Islam, especially Umayyad and Abbasid art, and Arabic calligraphy. He is the author of The Rise of Islamic Calligraphy (2010), Midad: The Private and Intimate Lives of Arabic Calligraphy (2017), and Power, Patronage and Memory in Early Islam: Perspectives on Umayyad Elites (2018, co-edited with Andrew Marsham). In 2010, he was awarded a Philip Leverhulme Prize.

| Theme | Architecture, Visual Art |

|---|

Acknowledgements

Introduction: A Day in the Life of Damascus

The Story So Far

The Present Book

1. Palimpsests in Stone and Layered Texts: The Multiple Histories of the Umayyad Mosque

The Mosque and its Historiography until the Ottoman Era

The Syrian Historiographical Tradition

Early Travel Relations and Geographical Works

The Mosque in the Abbasid and Fatimid Periods

The Fire of 1069 and the Later History of the Mosque

The Mosque since the Nineteenth Century

The Fire of 1893

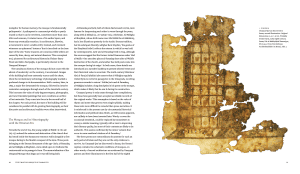

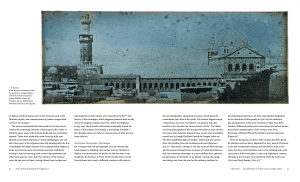

The Earliest Photographs of the Mosque

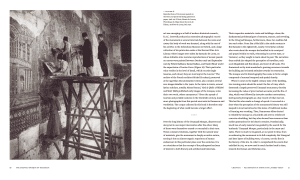

Restorations of the 1920s to 1960s

Photographs of the 1920s to 1940s

2.Tangled Memories: The Temple, Church, and First Mosque

The Cella of the Roman Temple

Layout of the Site

The 1962–63 Soundings

Identification of the Remains

Footprint of the Cella

Cella Elevation and Proportions

The Church within the Temenos and the First Mosque

Textual Narratives of Conversion

An Elusive Church

Location of the Church

The First Mosque and the Gate of the Khaḍrāʾ

The Church and the Cella

3. The Politics of Buildings: The Destruction of the Church and Construction of the Mosque

The Three Poems, the Foundation Inscription, and the Destruction of the Church

The Destruction as Divine Wisdom

The Church, Justinian II, and Maslama’s

Anatolian Campaigns

The (Lost) Foundation Inscription and the Date of the Mosque

The Aphrodito Papyri and the Logistics of Construction

Supply Networks for Labour and Materials

Construction Supervisors

Beyond Aphrodito

Justinian II and Umayyad Building Projects

Gethsemane and the Columns of Mecca

Justinian II and the Mosque of Damascus

The Byzantine Mosaicists at Medina

The Banū Manṣūr Between the Umayyads and Heraclians

4. Silenced and Imagined Pasts: The Church in the Fabric of the Umayyad Mosque

Scattered Echoes of the Church in the Mosque

The Transept

The Corner Towers

The Mosque Doors

Inventing the Relics of the Baptist

Absence of the Relics in Christian Sources

Muslim Traditions About the Relics

The Origins of the Bayt al-M l

The Bayt al-Māl in Arabic Sources

The Bayt al-Māl and the Typology of the Baptistery

5. A Vast Expanse of Splendour: Towards a Reconstruction of the Umayyad Mosque

Structure

Courtyard Arcades

Prayer Hall Arcades

The Transept

The Dome

Prayer Hall Façade

Windows and Door Hangings

Pavement and Floor Levels

The Bayt al-Māl Chamber

Merlons

Roofing

Columns and Colonnettes

Gates and Vestibules

The North Minaret

Water Reservoirs and Ablution Facilities

Ornament

Marble Dado

Mosaics

The Vine Frieze with Precious Stones

The Central Mihrab and Minbar

The Mosaic Inscription

Ceilings

Lamps, Lighting, and Incense

Paint on Capitals and Columns

6. ‘Jewelled Embellishments Dazzle’: The Mosque and Umayyad Aesthetics

The Novelty of al-Wal d’s Building

Embodying Power

Work Procedures

Reshaping Building Types

Recasting Mosaic Forms

Poetic Composition and the Mosque

Mosaics, Empire and Polysemy

Paradise and Earthly Dominion

The Horizon of Judgement

The Art of Polysemy

The Craft of Perception

Al-Nābigha and the Intensity of Sacred Space

The Mosque as a Foil for the Qurʾan

Appendix 1

Three Umayyad Poems about the Mosque of Damascus and the Destruction of the Church Arabic Text and Translation by Nadia Jamil

Jarīr

Al-Farazdaq

Al-Nabigha al-Shaybānī

Appendix 2

The Description of the Great Mosque of

Damascus by al-Muqaddas in the Tenth century Arabic Text and Translation by Alain George

Notes

Bibliography

Index

Introduction:

A Day in the Life of Damascus

30 December 2010

It is rainy and cold today. As our car edges past the gentle slopes of the Anti-Lebanon mountains, I discover once again the distant vision of Damascus, this vast urban sprawl experienced until a generation ago on a more intimate scale, enclosed by orchards.

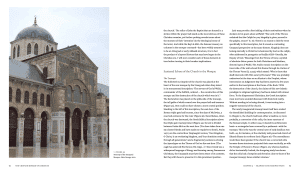

Moments later, walking through the old city, I catch a first glimpse of the Minaret of Jesus, which vanishes as I turn into

a winding alley. Street life is quietly running its course: a shop owner tenders change, delivery bicycles ring their bells, and children chat away after school. Reaching the massive Roman walls of the Umayyad Mosque, I pause to gaze at its Greek inscription, reaching the courtyard after a few more paces. Suddenly, the confined spaces of surrounding streets give way to the majestic expanse, bounded by arcades and a monumental façade, of a courtyard that frames the limitless grey skies above. The marble floor has been given added lustre by rainwater, making it vividly reflect the architecture.

Inside, some people seated on the carpeted floor rest or talk while others bow down in prayer. Tourists from Arab countries, Europe, and beyond amble about. An Ethiopian man in traditional dress peers through the metal grille that screens the

relics of John the Baptist. Repose and a certain awe inspired by harmonious monumentality; the sense of touching something very old, and alive: I have felt this way even since my first visit here, a long time ago, and still do so today. Little do I know that it will be years before I return—years during which the people of Syria will endure the worst of torments in their millions. To this day, the monument remains nearly unscathed—a meagre consolation in the face of such human suffering. But it stands as a witness to the long course of history, a poised counterpoint to the tragedies of our times.

The book you are holding is an investigation into this history. My core subject is the foundation of the mosque by the Umayyad dynasty (661‒750), just as the first century of Islam was drawing to a close. I also venture into the long pagan and Christian past over which the monument was inscribed; early eighth-century politics in the Muslim empire and beyond; the Umayyad state of the mosque and later alterations; and early Islamic aesthetics. Some of these concerns have an old pedigree. When the mosque was still

in its second century, the Damascene historian Ibn al-Muʿallā (d. 286/900) wrote a ‘Volume on the Story of the Congregational Mosque in Damascus and its Construction’, which is now lost but was cited by later writers.1 This is exceptionally early for a culture that has left precious little written output about art and architecture of any period, let alone its first century. Ibn Muʿallā’s work was the inaugural salvo of a historiographic tradition that would span a millennium. I will soon return to it; but, in order to situate what follows, let me begin with a brief overview of modern scholarship.

The Story So Far

The first substantial modern account of the mosque was published in 1855, a thousand years after Ibn al-Muʿallā,

by Josias Leslie Porter (1823–89) as a section of his book Five Years in Damascus (Figure 2).2 Other Europeans had furtively seen it before, bringing back with them hasty descriptions.3 But Porter, an Irish Presbyterian on a mission to convert local Jews, resided in Damascus long enough to get a solid footing in local society and thus managed to study it at close quarters. He also offered brief glimpses of its pre-Islamic past, foundation, and original state as related by the foremost medieval historian of the city, Ibn ʿAsākir (499–571/1105–76), whose work he consulted in manuscript form.

In 1890, Guy Le Strange, an Orientalist scholar trained in Paris and later based in Cambridge, translated a much wider range of relevant Arabic sources, especially travel accounts, thereby creating a small compendium that remains serviceable today.4 In the following years, structural studies and drawings were published by two architects, Archibald Campbell Dickie (1897) and Richard Phené Spiers (1900, based on a visit made in 1866). These efforts shared a link to the Palestine Exploration Fund, which published Le Strange’s book, invited Spiers to lecture on the mosque, mandated Dickie to Damascus—and, in 1900, published Charles Wilson’s diary of 1865 about the building. It must have been during these same years that the famous Swiss epigrapher and historian Max Van Berchem (1863‒1921) compiled his own detailed ‘archaeological notes’ about the monument, which were only printed posthumously, in 1937–38. Knowledge about the building thus slowly started to build up from different perspectives.

The first surveys of Islamic architecture appeared in the next decade. The one written by Henri Saladin (1907) offered

a basic account of the mosque with photographs predating

the fire of 1893 by Jules Gervais-Courtellemont. That by G.T. Rivoira devoted a longer passage to the site, with reflections on its history before and after the Umayyad period.5 During the same years, an important new body of evidence surfaced with Harold Idris Bell’s edition and partial translations of the British Museum’s collection of papyri from Aphrodito in Egypt, some of which pertained directly to the construction of the mosque. They remained largely unexploited until the end of the century, when Federico Morelli gathered and described the fragments about Umayyad building projects.6 Between 1921 and 1924, Carl Watzinger and Karl Wulzinger published an extensive study of the site through its pre-Islamic and Islamic history—the first of its kind—and inaugurated, along with René Dussaud in 1922, scholarship on the Temple of Jupiter, which has given its walls and gates to the mosque.7 These publications set the monument in its Roman context and furthered the documentation of relevant inscriptions and textual sources.

In 1932, less than eight decades after Porter’s book, the modern historiography of the mosque reached its first major milestone with the publication of K.A.C. Creswell’s two-volume Early Muslim Architecture (a second, revised edition appeared in 1969). By then, the Ottoman Empire had been recently abolished and the French Mandate over Syria and Lebanon facilitated access to the site for Europeans. With this work, Creswell, an electrical engineer by training, demonstrated his outstanding acumen as an architectural historian. Over some sixty pages of the first volume, he scrutinised, dated, and critically assessed every aspect of the mosque against textual sources. Creswell notably exposed as untenable the theories of Watzinger, Wulzinger, and Dussaud about the prayer hall as a conversion of the church. He also provided a series of detailed plans and elevations with accomplished draughtsmanship.

This volume of Early Muslim Architecture, on the Umayyads, concluded with a study of the mosaics by the art historian Marguerite Van Berchem (1892‒1984), Max’s daughter, in which she sought to distinguish Umayyad parts from later restorations and, again, collect sources about them. Most of these mosaics had been uncovered only four years earlier, in 1928, through her efforts combined with those of Victor Eustache, known as de Lorey (1875‒1953), who also published a series of articles setting them in the context of Christian wall mosaics.8 The spectacular discovery and its diffusion soon turned the mosaics into the main centre of interest for studies on the mosque.

Whereas Creswell had an innate fascination for buildings— as Robert Hamilton put it, for him, ‘human beings and

their affairs were part of the evidence, not vice versa’—his contemporary Jean Sauvaget (1901–50) had a rare instinct for history.9 Although he only published brief remarks about the Damascus mosque, his seminal study on the Umayyad Mosque of Medina (1947) established a template for the parsing of complex Arabic sources to reconstruct an early Islamic monument. He also put forward the provocative and somewhat overstated argument that such key architectural features as the mihrab and minbar were invented for courtly ceremonial and audiences, which he saw as prime functions of the early mosque.10 At around the same time, in contrast, Ugo Monneret de Villard (1881‒1954) argued that the concave mihrab and architectural emphasis on the transept at Damascus both reflected ‘thinking of a theological order’.11 But this work was only published posthumously, in 1966.

Judging from their verbal jousts in various publications, Creswell could be seen as Sauvaget’s nemesis. It is a testimony to the achievements of both scholars that their works should remain indispensable references to this day—and this posterity is likely to endure, given that they gathered much primary evidence on their respective subjects, some of it now lost. Another of their contemporaries is mostly remembered for courting controversy. Henri Lammens (1862–1937) was a Jesuit priest from Ghent in Belgium who settled in Beirut at the age of fifteen. Equipped with a thorough command of Arabic, he was the first scholar (and to a large extent the last) to highlight the Umayyad caliph al-Walīd’s destruction of the church at Damascus in an article of 1925.12 In this work, he also adduced to the study of the Umayyad Mosque some fundamental documents: a few verses from court poems by al-Farazdaq and al-Nābigha al-Shaybānī that commemorated this event; and a testimony datable to around 670 ascribed to ‘Arculf’ by Adomnán, abbot of Iona in Scotland (d. 704).13 The profound hostility of Lammens towards Islam tainted his work, making

it distinctly unpalatable to the modern reader. His outlook reflects a discourse current in Lebanese Christian circles at the time, its tone probably aggravated by famine and Ottoman exactions against the Jesuits during the First World War. Its undeniable biases should, however, not obscure Lammens’ knowledge of the sources especially as these inclinations were partly mitigated in his treatment of the Umayyads, because of their Syro-centrism.14

In 1948, the year after Sauvaget published La mosquée omeyyade de Médine, a small Arabic pamphlet inaugurated an important strand in scholarship. The Great Mosque of Damascus: Some of its Developments until the Year 730 A.H. was written in Arabic by the Syrian scholar Ṣalāḥ al-Dīn al-Munajjid (1920– 2010).15 Al-Munajjid was born in the vicinity of the Umayyad Mosque to a father, ʿAbd Allāh, who had trained as a sheikh under several Damascene scholars. After legal studies at Damascus and the Sorbonne, from 1955 to 1961 he was director of the Institute of Arabic Manuscripts, founded in 1948 by the Arab League in Cairo. In this role, he established meticulous standards for text editions, launched a specialised journal and travelled the world in search of original works to record on microfilm. He taught briefly at Princeton (1959–60), then settled for a decade and a half in Beirut, where he established the Dār al-Kitāb al-Jadīd publishing house. Following the start of the Lebanese civil war in 1975, he moved to Jeddah where he would live for another thirty-five years.16

Throughout his prolific career, al-Munajjid retained a particular interest in the history of his home city. In 1954, he edited al-Rabaʿī’s Virtues of Syria of Damascus and initiated work on the edition of Ibn ʿAsākir’s History of Damascus. He published two volumes in the same year; the second of these was translated into French in 1959 with a useful critical apparatus by Nikita Elisséeff. This was only a small part of Ibn ʿAsākir’s work, which would be edited only decades later. Al-Munajjid also published in 1967 a valuable anthology of texts about the history of Damascus: The City of Damascus in the Writings of Muslim Geographers and Travellers, including several extracts from unpublished manuscripts.17

From the 1960s onwards, other Syrian scholars gathered primary evidence relevant to the mosque. Muṭīʿ Ḥāfiẓ and ʿAlī al-Ṭānṭāwī collected medieval and modern sources about its history, while ʿAbd al-Qādir al-Rīḥāwī published brief reports about mosaic restorations and archaeological soundings undertaken at the time.18 In 1987, the collected poems (dīwān) of al-Nābigha al-Shaybānī, al-Walīd’s court poet, were edited for the first time in Damascus by ʿAbd al-Karīm Ibrāhīm Yaʿqūb.19 The complete publication of Ibn ʿAsākir’s work, a project re-attempted by several scholars after al-Munajjid, was finally brought to completion through the efforts of ʿUmar al-ʿAmrawī and his collaborators.20 The wide availability of this edition, published by Dār al-Fikr in Beirut from 1995 to 2001, is of fundamental importance to the study of the mosque. Many of these modern writers were driven by a Syrian nationalist or patriotic outlook, combined for some, such as Ḥāfiẓ, with an interest in the Islamic credentials of Damascus. They were also seeking to remedy, by integrating the methods of modern scholarship, the break from the Syrian historiographical tradition that had occurred after the end of the Ottoman Empire.

Meanwhile, building partly on Creswell’s scholarship, the modern study of Islamic art and architecture was growing

in scope and sophistication in Europe and the United States.

In a short passage in his seminal Arab Painting, published in 1962, Richard Ettinghausen proposed the first overarching interpretation of the famed mosaics at the mosque, which he saw as a representation of the Islamic empire. A few years later, in 1967, Eva Surpan-Boersch argued that these were paradisiacal landscapes, a theory developed further by Barbara Finster in 1970–71, and again by Klaus Brisch in 1988. In 1971, Lucien Golvin published a book-length study of Umayyad architecture, including a long section on the mosque that discussed both of these interpretations without seeking to resolve their contradictions. More than his predecessors,

he also sought to place the whole monument—not just the mosaics—in their broader artistic context.21

Between the late 1980s and mid-2000s, Klaus Freyberger devoted a series of articles to the remains of the Roman temple at Damascus, which offered a more systematic study of its ornamental styles and phases of construction. Further contributions were made from this period to the 2010s by Ernest Will on the temple, Mab Van Lohuizen-Mulder on the Umayyad mosaics, Luitgard Mols on the gates, and François Bogard on the later mosaics inside the transept.22 A book by Talal Akili (2009) contains architectural plans and elevations with extensive measurements and stone-by-stone drawings. This visual survey, carried out in 1996–2000 by a team of forty-five architects, is a valuable resource for the study of the building.23 Gérard Degeorge has produced a lavish volume (2010) with a well-documented text articulated around the photographs of the author. It is also during this last period that the next milestone in the historiography of the mosque was published: Finbarr Barry Flood’s The Great Mosque of Damascus: Studies in the Making of an Umayyad Visual Culture (2000). With this study, Flood delved into the complex history and textual memories of the monument to an unprecedented depth. He notably established the importance of the now lost vine frieze in the prayer hall (al-karma), highlighted the connotations of its pearl motifs with light, exhumed textual materials about a forgotten gate, a water clock and a colonnade on the qibla wall and introduced elements of comparison between the topography of this site and Constantinople. Flood’s work has given a new textural density to our understanding of the mosque. It has also helped to move analysis away from the mosaics, the main focus of attention since the 1960s, towards a history that engages fully with other parts of the structure. The present study blazes a similar trail, but with different ends.

scholarship; see Hoyland and Waidler,

‘Adomnán’s De Locis Sanctis’.

14. See on this question Irwin, For Lust of

Knowing, 201–2.

15. Masjid Dimashq: Dhikr shayʾ mimmā istaqarra

ʿalayhi al-masjid ilā sanat 730 h.

16. Biographical remarks after Yāfī, ‘Ṣalāḥ al-Dīn al-Munajjid’, especially 1–4; Ḥalwajī, ‘Ishāmāt’, especially 48–52.

17. Madīnat Dimashq ʿinda al-jughrafiyyīn wa’l- raḥḥālīn al-muslimīn.

18. Ḥāfiẓ, Al-jāmiʿ al-umawī; Ḥāfiẓ, Ḥarīq al-jāmiʿ al-umawī; Ṭānṭāwī, Al-jāmiʿ al-umawī; Rīḥāwī, ‘Fusayfisāʾ al-jāmiʿ’; Rīḥāwī, ‘Ishām’.

19. For the present work, I have consulted the 1996 edition by ʿUmar Fārūq al-Ṭabbāʿ.

20. See al-ʿAmrawī’s remarks in Ibn ʿAsākir, Tārīkh, 1:37–48; Mourad, ‘Publication History of TMD’; Khalek, ‘Prologue’.

21. Ettinghausen, Arab Painting, 22–28; Börsch- Supan, Garten-, Landschafts- und Paradiesmotive, 118–20; Finster, ‘Die Mosaiken’, 117–21; Brisch, ‘Observations’; Golvin, Essai, chapter 3.

22. Freyberger, ‘Untersuchungen’; Freyberger, ‘Das Heiligtum’; Freyberger, ‘Im Zeichen des Höchsten Gottes’; Will, ‘Damas antique’; Van Lohuizen-Mulder, ‘The Mosaics’; Mols, ‘Panels and Rosettes’; Bogard, ‘Autour d’une mosaïque’.

23. The original Arabic appeared in 2008 and the English translation, which I have consulted for this book, in 2009. A German translation was published in 2016 by Nünnerich-Asmus Verlag.

The book is sumptuously illustrated, enjoyable to read, and not too expensive for the high-quality art history book it is. It enters among the must-haves for scholars and libraries devoted to late antiquity, early Islam, art history, and Islamic studies.

Journal of Islamic Studies

Read full review

‘Although George’s book in not the first study of the building, nor likely to be the last, his book achieves a synthesis of earlier literature that is unprecedented in scope. Richly illustrated handsomely produced, it is a testament to the author’s creativity and resourcefulness, which have resulted in a landmark study.’

Sean W. Anthony, Burlington Magazine

‘…this sumptuously illustrated and beautifully produced book…shows us that there is still much to learn from buildings we thought we knew. Alain George fires the imagination through his careful but evocative reimagining.’

Scott Redford, Times Literary Supplement

Read full review

‘Alain George’s illuminating new study shows us that the Umayyad Mosque has always been claimed by rival faiths.’

Sameer Rahim, Apollo Magazine

‘Document of a Damascene Conversion’

History Today

‘George examines the mosque in great detail, illustrating practically every section of the building, the quality of the photographs almost making it seem like the reader is actually there looking at each part of the building…’

Asian Review of Books

‘In this comprehensive biography of the Umayyad Mosque, Alain George explores a wide range of sources to excavate the dense layers of the mosque’s history, also uncovering what the structure looked like when it was first built with its impressive marble and mosaic-clad walls.’

Asian Art Newspaper

‘This superlative book is to be highly recommended. George is a gifted writer, his book being very readable and informative, with multiple illustrations, such as old watercolours and photographs.’

Evangelicals Now

‘For the first time we have a book which does full justice to the Umayyad mosque in Damascus. Alain George has used text, archaeology and perhaps most revealingly, old photographs to produce a rich scholarly, readable and exciting account of the mosque. This book marks a major advance in our understanding of the building.’

Hugh Kennedy, author of The Caliphate: A Pelican Introduction

‘Alain George provides a vivid picture of the Umayyad mosque as it was designed and erected at the very beginning of the eighth century. This book is a scientific and aesthetic tour de force, and will become an indispensable reference for historians and architecture lovers.’

Mathieu Tillier, author of L’invention du cadi. La justice des musulmans, des juifs et des chrétiens aux premiers siècles de l’Islam

‘This is an important study that brings many fresh insights to a building that has already generated much scholarship. Alain George is sensitive to the need to resolve discontinuities between primary textual accounts and the physical record of the standing structures and excavated material. This book will be read by specialists, but will also gain a wider readership among researchers engaged with similar problems in other regions and historical periods.’

Marcus Milwright, author of The Dome of the Rock and its Umayyad Mosaic Inscriptions

‘Borrowing the model of the palimpsest, George’s The Umayyad Mosque of Damascus: Art, Faith and Empire in Early Islam takes the reader on a vivid tour of the renowned mosque’s history, meaning, and significance.’

Stephennie Mulder, Hyperallergic

Read full review

New Podcast: The Jewel of Damascus with Alain George – The Barakat Trust

Our work relies on the generous support of our donors. Any contribution, no matter how small, helps us achieve our aims.